By Charlayne Hunter Gault – Although the American Civil Rights Movement has been described as “one of the defining moments in US history,” a report by the Southern Poverty Law Center tells us that civil rights education in America “boils down to two people and four words: Rosa Parks, Dr. King and ‘I have a dream.” The Civil Rights Movement is especially relevant today as social justice protests rage in the streets.

By Charlayne Hunter Gault – Although the American Civil Rights Movement has been described as “one of the defining moments in US history,” a report by the Southern Poverty Law Center tells us that civil rights education in America “boils down to two people and four words: Rosa Parks, Dr. King and ‘I have a dream.” The Civil Rights Movement is especially relevant today as social justice protests rage in the streets.

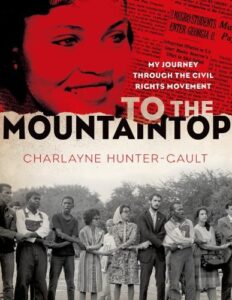

Well, I am hoping that my book, “To The Mountaintop: My Journey Through the Civil Rights Movement,” published by Roaring Brook Press and The New York Times, will help change how young people understand the Movement. The book is designed, in part, to help young people understand that, indeed, “there can be no progress without struggle,” as Frederick Douglass put it in words that surely emboldened that generation of high school and college students in the American South. Through their struggle, they changed the face of America as it brought the South and its racist, separate and unequal laws in line with the rest of the country that guaranteed liberty and justice for all. And while Franz Fanon, that other Freedom fighter in another country, told us that each generation must find its own cause and embrace or deny it, the lesson of the US Civil Rights Movement is that young people can make a difference. Their struggle led to the election of the first Black president, who acknowledged that he stood “on the shoulders of giants.” What is required, to be sure, is courage, commitment and righteous human values, in the case of the students of the Movement— values that were informed by the principles freedom, justice and equality. Values that my generation was prepared to die for, and far too many did, as I chronicle in the book. Far too many also paid a price of being beaten, tortured and thrown into overcrowded and cold jail cells, with few amenities. And yet, when the first group of young Freedom Riders left Washington, D.C. to test the law forbidding segregation in travel across state lines, so dedicated were they to their cause, they were prepared to die and left their wills behind in the case of that dreadful eventuality.

And while many of them were exposed to physical acts of hatred and brutality by racist white mobs, they kept on keepin’ on, in one of the lines they spoke or sang during that time.

They also sang “Ain’t gonna let nobody turn me ‘roun,” and they meant it.

I tell their stories, as well as my own, as I took my place not on a Freedom Ride or sitting in at a lunch counter or registering black people to vote for the first time in their lives, but walking through a hostile white mob to get the education at the state University of Georgia that as a citizen I was entitled to, but which I and thousands of Black students in Georgia had been denied, even though it violated the 1954 Supreme Court decision outlawing the lie of “separate but equal.” In the book, I describe the reality of “separate but equal” in my own elementary school, which got the hand-me-down textbooks, often with pages missing, from the white schools. And many of the other indignities Blacks suffered because of separate and far from equal.

And while I hope that the young people for whom this book was written will be informed by this history and the value of fighting for what you believe in, I hope they will also appreciate the words of the philosopher George Santayana: “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

Look around the United States today and listen to some of the virulent rhetoric of the immigration debate or at some of the not-so-veiled racism in politics and public discourse and think about what they are doing to a country that once identified with the words inscribed on the Statue of Liberty:

“Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free;

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore,

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tossed to me

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

Are these words still relevant to the increasingly Black and brown homeless, tempest- tossed, huddled masses yearning to breathe free? And what will it take to make those words a reality for them, and to help all Americans realize the possibilities of the American Dream?

Whatever it takes, there are lessons from the Civil Rights Movement that may inform a new generation. Not to sit in at lunch counters or to go on  Freedom Rides, but to determine their own path, emboldened by the victories of young people like themselves at a different time.

Freedom Rides, but to determine their own path, emboldened by the victories of young people like themselves at a different time.

It is my hope that To The Mountaintop will, in the words of the late Edward R. Murrow, “illuminate, educate and inspire.”

Click Here to purchase “To the Mountaintop: Teaching the Civil Rights Movement.”

Share your thoughts